American history is filled with writers whose genius was underappreciated—or altogether ignored—in their lifetime. Most of Emily Dickinson’s poems weren’t discovered and published until after her death. F. Scott Fitzgerald “died believing himself a failure.” Zora Neale Hurston was buried in an unmarked grave. John Kennedy Toole won the Pulitzer Prize 12 years after committing suicide.

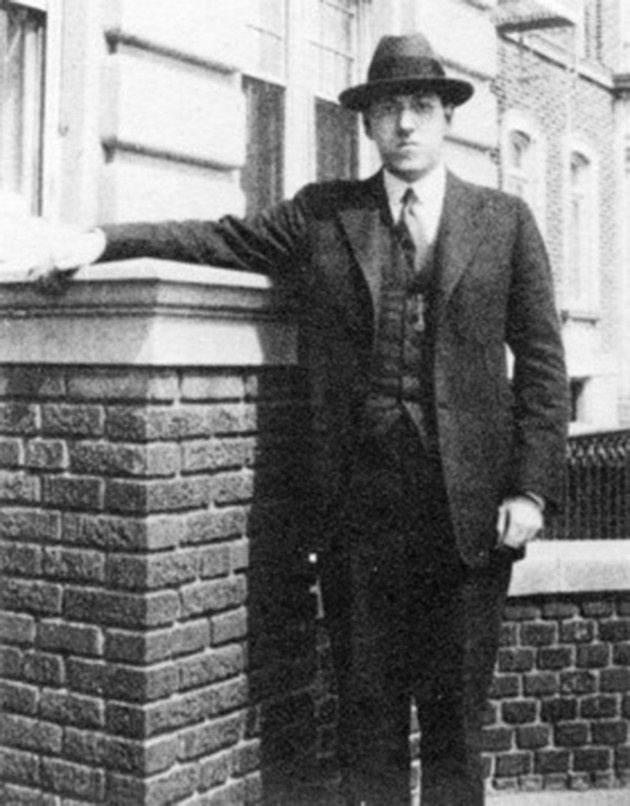

But no tale of posthumous success is quite as spectacular as that of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, the “cosmic horror” writer who died in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1937 at the age of 46. The circumstances of Lovecraft’s final years were as bleak as anyone’s. He ate expired canned food and wrote to a friend, “I was never closer to the bread-line.” He never saw his stories collectively published in book form, and, before succumbing to intestinal cancer, he wrote, “I have no illusions concerning the precarious status of my tales, and do not expect to become a serious competitor of my favorite weird authors.” Among the last words the author uttered were, “Sometimes the pain is unbearable.” His obituary in the Providence Evening Bulletin was “full of errors large and small,” according to his biographer.

Nowadays, it’s hard to imagine Lovecraft faced such poverty and obscurity, when regions of Pluto are named for Lovecraftian monsters, the World Fantasy Award trophy bears his likeness, his work appears in the Library of America, the New York Review of Books calls him “The King of Weird,” and his face is printed on everything from beer cans to baby books to thong underwear. The author hasn’t just escaped anonymity; he’s reached the highest levels of critical and cultural success. His is perhaps the craziest literary afterlife this country has ever seen.

Which isn’t to say Lovecraft’s reanimation is simply a feel-good story. His rise to fame has brought both his talents and flaws into sharper focus: This is a man who, in a 1934 letter, described “extra-legal measures such as lynching & intimidation” in Mississippi and Alabama as “ingenious.” On the 125th anniversary of Lovecraft’s birth on August 20, 1890, the author’s legacy has never been more secure—or more complex. Stephen King calls him “the 20th century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale,” and yet Lovecraft was also unarguably racist—two distinct labels that those studying and enjoying his works today have had to reconcile.

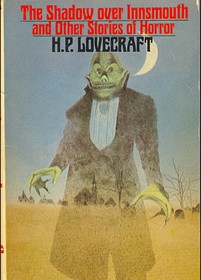

But it’s Lovecraft’s fiction—70 stories, plus a number co-written with other authors—that provide the basis for his reputation. The spirit of these tales is perhaps most aptly conveyed by the meme with his face and the caption, “AND THEY LIVED HAPPILY EVER AFT—JUST KIDDING, THEY’RE ALL DEAD OR INSANE.” The titles of his stories also give a sense of the mood: “The Lurking Fear,” “The Terrible Old Man,” “The Rats in the Walls.”

Everyday scenarios held little allure for Lovecraft. “I could not write about ‘ordinary people’ because I am not in the least interested in them,” he once wrote. And so, he wrote about the bizarre: cannibalism, reanimation, self-immolation, murder, madness-inducing meteors, human-fish hybrids, aliens, and, in the case of “The Festival,” a “horde of tame, trained, hybrid winged things that no sound eye could ever wholly grasp, or sound brain ever wholly remember.” Another tale, 1924’s “The Shunned House,” offers a vaguely happy ending: an image of birds returning to an “old barren tree.” But that’s only after the narrator’s uncle transforms into a “dimly phosphorescent cloud of fungous loathsomeness … who with blackening and decaying features leered and gibbered at me, and reached out dripping claws.”

Lovecraft sold these stories for paltry sums to pulp magazines like Weird Tales and Astounding Stories. He also made a bit of money revising the work of other authors. But it never amounted to much. Leslie Klinger, the editor of The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, describes him as the “quintessential starving artist.” And, though Lovecraft developed a devoted cult following—he corresponded with a young Robert Bloch, decades before Bloch wrote Psycho—critical acclaim eluded him, too. A few years after he died, the New Yorker critic Edmund Wilson wrote, bluntly, “Lovecraft was not a good writer,” adding, “The only real horror in most of these fictions is the horror of bad art and bad taste.”

But even as Wilson derided his work, the author’s fans and friends hustled to get his work into print. As the Lovecraft biographer S.T. Joshi recounted in a 2013 speech, one young fan took a bus ride from Kansas to Rhode Island after Lovecraft’s death to ensure that the author’s papers were donated to Brown University. Other friends launched a publishing house, Arkham House, with the express purpose of publishing Lovecraft’s stories.

“He was in the canon of American literature right there with Poe and Hawthorne and Melville and Henry James and Willa Cather and Edith Wharton,” he said. “He had made it.”

But Lovecraft’s critical comeback is only half of the story. The other is his conquest of popular culture.

Lovecraft ranks among the most tchotchke-fied writers in the world. Board Games. Coins. Corsets. Christmas wreaths. Dice. Dresses. Keychains. License-plate frames. Mugs. Phone cases. Plush toys. Posters. Ties. Enterprising fans have stamped the name “Cthulhu” (Lovecraft’s most famous creation; a towering, malevolent, multi-tentacled deity) or other Lovecraftian gibberish on nearly every imaginable consumer product. And it’s not just merchandise. It’s apps and movies and podcasts. It’s a bar in New York City called Lovecraft. It’s a parody musical called “A Shoggoth on the Roof.” It’s a celebrity fan club that includes Guillermo Del Toro, Neil Gaiman, Junot Diaz, and Joyce Carol Oates. It’s Lovecraft festivals in Stockholm, Sweden; Lyon, France; Portland, Oregon; and Providence.

Speaking of Providence, where I live, the town has recently shaken off decades of apathy toward its literary superstar. Providence now has an intersection named for Lovecraft, a Lovecraft bust, Lovecraft walking tours, Lovecraft read-a-thons, a Lovecraft story-writing contest, and an endowed fellowship at Brown University “for research relating to H. P. Lovecraft, his associates, and literary heirs.” Last month brought the opening of a Lovecraft-themed “weird emporium and information bureau,” where you can buy “CTHULHU FHTAGN” t-shirts and “I AM PROVIDENCE” bumper stickers.

The store’s co-owner, Niels Hobbs, also runs the NecronomiCon Providence convention where S.T. Joshi delivered his 2013 speech. He recently told me that the balloon of Lovecraft’s popularity is bound to burst. “I just can’t see how it can continue to sustain itself at this rate,” he said. “But, that being said,” he added, “it doesn’t seem to slow down.”

So, why does any of this matter? Well, in Providence, 2013’s convention brought an estimated $600,000 to city businesses. And this year’s festival, from August 20 through 23, promises to be even bigger. There will be concerts, bus tours, art exhibitions, board games, readings, LARPing, a costume ball, and panels with titles like “Mechanics of Fear,” and “Oh, The Tentacles!” If you’re someone who keeps track of events celebrating American authors—Hemingway Days, in Key West; Twain on Main, in Hannibal, Missouri; or The Tennessee Williams/New Orleans Literary Festival—mark down the NecronomiCon as the one featuring a “Cthulhu Prayer Breakfast.”

These writings leave Lovecraft fans in an uncomfortable spot. Leeman Kessler, who plays Lovecraft in the popular “Ask Lovecraft” YouTube series, has written an essay, “On Portraying a White Supremacist,” in which he says, “As long as I take money for playing Lovecraft or accept invitations to conventions or festivals, I think it is my moral duty to stare unflinchingly at the unpleasantness.” In 2011, the World Fantasy Award-winning novelist Nnedi Okorafor wrote a blog post calling attention to Lovecraft’s poem, “On the Creation of Niggers.” “Do I want ‘The Howard’ (the nickname for the World Fantasy Award statuette…) replaced with the head of some other great writer?” she wrote. “Maybe … maybe not. What I know [is] I want … to face the history of this leg of literature rather than put it aside or bury it.”

Last year, a petition demanding Octavia Butler replace Lovecraft as the face on WFA trophies received more than 2,500 signatures. A counter-petition soon followed, titled, “Keep the Beloved H.P. Lovecraft Caricature Busts (‘Howards’) as World Fantasy Award Trophies, Don’t Ban Them to be PC!” Similar exchanges play out regularly on the many social media pages dedicated to Lovecraft.

But as vexing as Lovecraft’s racism is for fans, his views are also one of the most useful lenses for reading his work. In March, Leslie Klinger delivered a lecture on Lovecraft at Brown University’s Hay Library, home to the world’s largest collection of Lovecraft papers and other materials. Toward the end of his remarks, Klinger—without excusing or defending Lovecraft’s racism—refused to separate it from his achievements. Lovecraft “despised people who weren’t White Anglo-Saxon Protestants,” he said. “But that powers the stories … this sense that he’s alone, that he’s surrounded by enemies and everything is hostile to him. And I think you take away that part of his character, it might make him a much nicer person, but it would destroy the stories.”

In this light it is possible to perceive Howard Lovecraft as an almost unbearably sensitive barometer of American dread. Far from outlandish eccentricities, the fears that generate Lovecraft’s stories and opinions were precisely those of the white, middle-class, heterosexual, Protestant-descended males who were most threatened by the shifting power relationships and values of the modern world.

My feelings on Lovecraft—as a bibliophile, a lover of Providence history, a Jew, a fan of his writing, a teacher who assigns his stories—are complicated. At their best, his tales achieve a visceral eeriness, or fling the reader’s imagination to the furthest depths of outer space. Once you develop a taste for his maximalist style, these stories become addictive. But my admiration is always coupled with the knowledge that Lovecraft would have found my Jewish heritage repugnant, and that he saw our shared hometown as a haven from the waves of immigrants he saw as infecting other cities. (“America has lost New York to the mongrels, but the sun shines just as brightly over Providence,” he wrote to a friend in 1926.)

I haven’t made peace with this tension, and I’m not sure I ever will. But I have decided that perhaps he’s the literary icon our country deserves. The stories he conjured, in many ways, say as much about his bigotry as they do his genius. Or, as Moore writes, “Coded in an alphabet of monsters, Lovecraft’s writings offer a potential key to understanding our current dilemma.”