This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

Coronavirus cases continue to rise here in the United States, where there are now an average of 125,000 daily infections, with cases soaring in areas with low vaccination rates.

We’re joined now by John Barry. He’s professor at Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans. He’s the author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, his latest piece for The Washington Post is headlined “What history tells us about the delta variant — and the variants that will follow.”

We last spoke to John in July of 2020. At the time, he was warning the pandemic could get, quote, “much, much worse.” Well, over the last year, over three-and-a-half million people have died around the world, including nearly half a million in the United States.

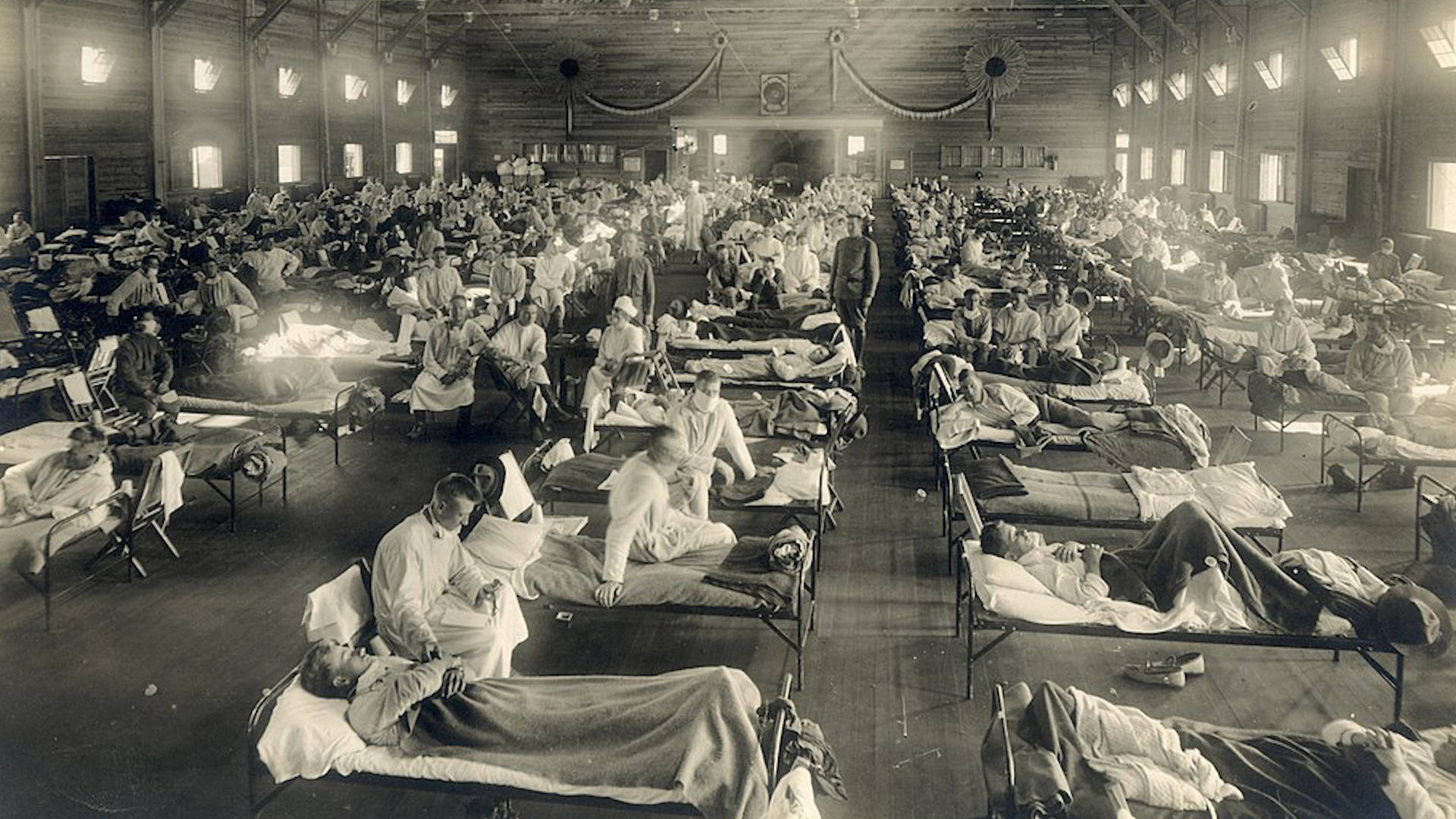

So, John Barry, so sadly, your prediction was right. Talk about what you learned from the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic that we should learn from today.

JOHN BARRY: Well, it’s not just 1918. There were pandemics 1889, 1957, ’68, even 2009, and they all behaved the same way. 1918 is the most dramatic. You had a first wave that was very mild. One statistic encapsulates that: 10,313 sailors in the British Grand Fleet got sick in the first wave; only four of them died. But that first wave was not particularly transmissible. The virus picked up an ability to transmit much more efficiently and also became much more lethal. That’s where you get the 50 to 100 million dead, two-thirds of them in the second wave. There was a third wave. The virus continued to mutate. Third wave was actually less lethal than the second wave. And after that, people’s immune systems adjusted to the virus. Possibly, the virus mutated in a direction of mildness.

But you saw a similar pattern in ’57. Actually, the deadliest month in the United States from that pandemic was actually in 1960, when a vaccine was available and when people had already adjusted — you know, their immune systems had already seen the virus. So, a variant did that in 1960.

1968 is a little more complicated. And the U.S., in the first wave in 1968, had the most deaths. But in Europe in 1969, again, after a vaccine, after a lot of people had been exposed to the virus and had natural immunity, that was the deadliest year. 2009, similar thing happened.

So, this is not unusual, what we’re going through. The question is whether the next variant is going to be even more transmissible and possibly more virulent, or whether it’s going to be toned down. We are going to — by the time the next variant emerges and spreads widely, we are going to have a very large majority of the country exposed or vaccinated. We’ve already got 70% with at least one dose, of adults. Of about 90 to 100 million people who aren’t vaccinated, you know, a lot of them are going to be exposed. So, in a few months, we’re going to have over 80% of the population either fully vaccinated or having been naturally exposed.

There will be more changes in the virus. The question is what direction it’s going to go. We don’t know. Nobody can predict that. I’m hoping that things will calm down in a more permanent way in a couple months, because, again, we’ll have well over 80% of the population probably either vaccinated or naturally exposed.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And on the basis of your research on these previous pandemics, John Barry, can you talk about what you think needs to be done, both within the U.S. but also globally, in order to prevent the virus from mutating further and potentially, eventually, entirely evading the vaccines?

JOHN BARRY: Well, obviously, the only way you can prevent the virus from mutating is to prevent it from infecting people. So that means vaccination, and, you know, social distancing and so forth when you don’t have the vaccination. You know, the more opportunities — it’s just like rolling dice. The odds of not getting snake eyes if you roll the dice once are pretty good. But if you roll the dice 10,000 times, you’re going to get a lot of snake eyes coming up. So, the fewer people infected by the virus, the less opportunity it has to mutate.

You know, clearly, it does have the ability to escape both natural immunity and the vaccine. And eventually, it’s going to do that. I do think that will happen slowly enough that the vaccines will be able to keep pace. You know, we’ll probably need another shot every few years. The virus mutates much less rapidly than influenza.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And on that question of needing a another shot every few years, what about this question that’s been raised about administering booster shots as soon as the fall here in the U.S.?

JOHN BARRY: Well, you know, honestly, I have some self-interest in that. You know, my wife and I are both over 70. There are ethical questions in terms of vaccine distribution around the world. You know, I would say the vaccines in the United States are here. I don’t see an ethical problem in — well, maybe I would see one, actually. From a strictly medical standpoint, strictly medical, yeah, I think it makes good sense to administer a booster.

There was a study, as you probably — as I’m sure you know, and probably your audience knows, that just came out, that said the Pfizer vaccine has declined to 42% effectiveness in July in preventing illness. It’s still extremely, extremely effective in preventing serious illness, hospitalization, ICU admission, death and so forth. But from a strictly medical standpoint, I think it would probably make sense to have a booster. From the ethical standpoint in terms of distributing it to the rest of the world, that’s a different question.

AMY GOODMAN: John Barry, you know, at the beginning of our show in headlines, we talked about what’s happening in Tennessee, and it’s happening in other places, too. You have these meetings where schools, for example, are deciding on mask mandates, and extremely hateful anti-mask protesters threatening doctors, public health professionals, who say masks are very important right now. That happened last night at a public meeting. Can you talk about the issue of masks? Back in a hundred years ago with the Spanish flu, were they used? And then, going forward in history, and this kind of vitriol and the issue of misinformation?

JOHN BARRY: Well, they were used in 1918. They actually — scientists ran experiments with masks even before the pandemic, just before the pandemic, and demonstrated that masks on people who were sick protect people who were around them. They actually knew that scientifically in 1918.

For the general public, masks, in a lot of cities, were required. Those masks were not very good. Generally, they were just layers of gauze, not even secured at the chin. And studies afterward showed that those masks were not very good, useful for the general public, and not worth doing.

In terms of the acceptance, however, I think there was some pushback, but I think what pushback there was has been greatly exaggerated today. You know, back then, that virus was much more lethal than what we’re facing. It was killing children under 10, and particularly children under 5. It was extraordinarily lethal. You know, two-thirds of the total deaths were probably people aged 18 to 50. And when people were seeing death all around them, sometimes someone, a neighbor, dying in 12 hours even, they took that virus seriously. Nobody believed it was a hoax. So, when measures were suggested that would protect you, there was very, very wide acceptance of those measures. So, the perception of the pandemic in 1918 was totally different than it is today.

You know, obviously, there is no logic to the position of the mask protesters. It’s absurd, what they’re saying. You know, you can’t smoke in a public place, because your smoking can hurt somebody else. You can’t even — you know, every state even requires seat belts, when the only person that you would hurt is yourself. So, to claim that this is an infringement on freedom is just nonsensical. But, you know, sense, unfortunately, has taken a holiday under the political polarization we’ve been seeing.

AMY GOODMAN: John Barry, we want to thank you so much for being with us, professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans, author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.

That does it for our show. A slight correction: Earlier, I said that our guest Sana Jaffrey’s father had died of COVID. In fact, she lost her mother-in-law to COVID in Indonesia.

Democracy Now! is currently accepting applications for our video production fellowship and our digital fellowship here in our New York City studio. The deadline is this weekend. You can learn more and apply at democracynow.org.

Democracy Now! is produced with Renée Feltz, Mike Burke, Deena Guzder, Messiah Rhodes, María Taracena, Tami Woronoff, Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Tey-Marie Astudillo, John Hamilton, Robby Karran, Hany Massoud and Adriano Contreras. Our general manager is Julie Crosby. Special thanks to Becca Staley, Miriam Barnard, Paul Powell, Mike DiFilippo, Miguel Nogueira, Hugh Gran, Denis Moynihan, David Prude and Dennis McCormick. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. Be safe. Wear a mask.