This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: The new coronavirus variant Omicron is spreading across the world at an unprecedented rate. The World Health Organization warns cases of the heavily mutated variant have been confirmed in 77 countries, and likely many others that have yet to detect it.

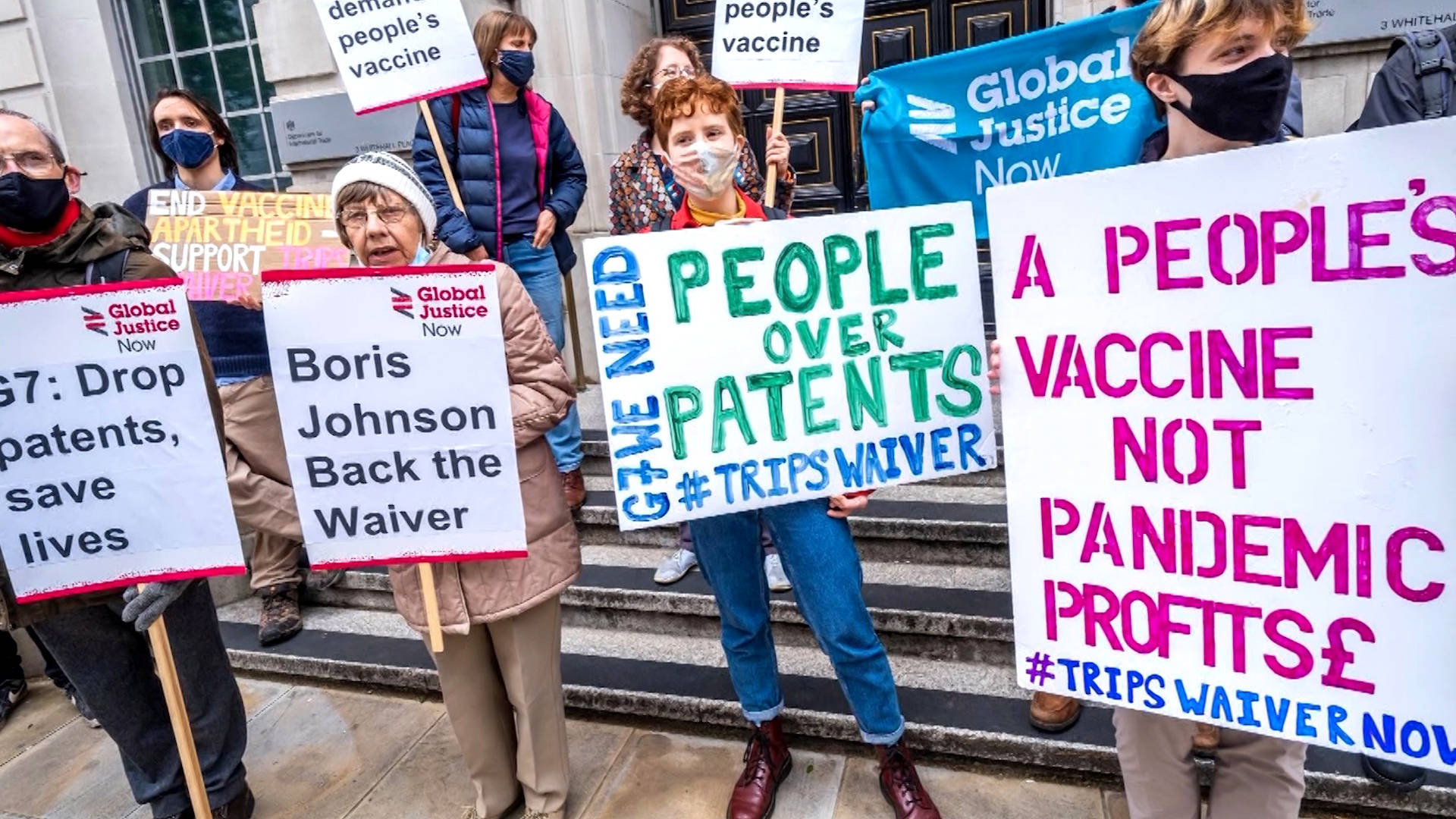

With international infections climbing, the Biden administration is facing renewed demands to follow through on his now seven-month-old pledge to ensure companies waive intellectual property protections on coronavirus vaccines and share them with the world.

Now a group of vaccine experts has just released a list of over a hundred companies in Africa, Asia and Latin America with the potential to produce mRNA vaccines to fight COVID-19. They say it’s one of the most viable solutions to fight vaccine inequity around the world and combat the spread of coronavirus variants, including Omicron.

For more, we’re joined by Achal Prabhala. He is coordinator of the AccessIBSA project, which campaigns for access to medicines in India, Brazil and South Africa. He’s the co-author of this new report.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Achal. Can you lay out this new list that you’ve compiled that shows that production of mRNA vaccines is possible outside the United States and Europe? What are these 100 companies around the world?

ACHAL PRABHALA: Thank you, Amy. It’s nice to be back.

I want to say that the backdrop to our report is Omicron. And what Omicron means, as we still figure out how infectious it is, how severe the infection that it causes is, what we know already are a few things. We know that all existing double-dose vaccines work less well against Omicron, which means that those who’ve had two doses of a Pfizer or Moderna vaccine in the United States need a booster. What we also know is that it’s highly transmissible and that it’s inevitably going to lead to a surge in cases, regardless of how severe they are.

What that in turn means for existing vaccine inequity, which is pretty deep — Nigeria has less than 2% of its population vaccinated as compared to countries in southern Europe, where the percentage is in the eighties — what it means is that vaccine inequity suddenly becomes worse. Why? Because everyone now needs more vaccines.

Our report is on mRNA vaccines, because they are a remarkable technology that we haven’t yet fully understood, meaning that they are not biology-based. They don’t require cells to be grown. And it means, therefore, that they can be made faster, more easily, and, therefore, by more companies than could make the previous vaccines we used to use before 2020.

We worked on finding companies that have the facilities and the quality standards and meet the technical requirements to make mRNA vaccines. And we found, to our astonishment, that there are at least 120 companies across Africa, Asia and Latin America who could be producing millions of doses of these vaccines, which, unfortunately, in the situation that we’re in — at a precipice — is really the only way by which we can get billions more vaccines into the world in the next three to six months.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Achal, we’ll get to details about those companies, but if you could talk first about your own vaccination experience? You’re in India. You received the AstraZeneca vaccine almost six months ago. What are your concerns now? You and your family all received AstraZeneca. What are your concerns about what will happen in January 2022?

ACHAL PRABHALA: I’m really concerned about us. I’m really concerned about the ones I love and the ones you love, Nermeen. And it’s because it’s — come January 1st, 2022, my clock will be reset. I was vaccinated six months ago with two doses of AstraZeneca. I’m one of the lucky people who lives in a poor country — I’m middle-class, I have credit cards. And yet, come January 1st, I will be as good as unvaccinated for the purposes of travel to Europe, to Israel, to a range of other countries, if I haven’t had a booster, which, by the way, India has no plans of giving out to people my age and does not have the supplies to give out even if it wanted to. I am deemed unvaccinated.

Other than that, the AstraZeneca vaccine has roughly about 10% protection against Omicron. This is something that I worry about not as much for myself as for my parents, who are in their seventies and eighties, for my sister, who’s physically disabled and requires round-the-clock nursing care. She can’t afford to self-isolate.

This is an astonishing situation for a large proportion of the world, which has only received two doses of a vaccine and does not have immediate prospects of a booster. When January hits and when Omicron spreads further around the world, we will have reset the clock, effectively. We’ll all be back to where we were on January 1st, 2021, at the beginning of this year: unvaccinated, vulnerable and afraid.

This is an untenable situation. To go through cycles like this is not how we plan to exit the pandemic, and it’s not how we will. Unfortunately, as bad as it seems today, it’s going to get worse. And unless something dramatically changes with vaccine supply, we are condemned to repeat these horrific cycles of surges and infections and unknowns, which not only have a — have not only caused a huge dramatic effect on people’s lives but also on people’s economies and livelihoods.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Achal, you said earlier that these hundred companies, over hundred companies that you’ve identified that could manufacture these mRNA vaccines, could produce millions of doses. Could you say specifically how many doses could be produced, in what period of time, if you have estimates, and what kind of impact that would have globally? As you pointed out, a massive country, the largest in Africa, Nigeria, has only 2% of its population vaccinated. What kind of impact would the rapid production of these vaccines have?

ACHAL PRABHALA: Nermeen, this is quite simple to explain. If the mRNA technology that Pfizer and BioNTech and Moderna have developed and deployed, to good effect so far, were to be shared with any number of these 120 companies around the world, we could vaccinate the world in as close to six months from now. This is simply a fact. It’s not theoretical. It’s based, in fact, on a model of existing partnerships that companies like Moderna have with very similar manufacturers, except they’re located in Spain instead of Bangladesh or Senegal or Tunisia.

What we’re asking for is for the same model that Moderna and Pfizer know — know — works to be implemented with as many companies as possible across the world, so that they can all start making the vaccines in the entities required. You need something like 2,500 square feet of space. You need a fairly small investment in order to create hundreds of millions of doses of vaccines. If we brought these companies together, if we provided them the technology and the licenses they require — something that Pfizer, BioNTech and Moderna, they hold in their hands, literally; they literally just have to open up their hands and allow other people to take what they have — and if they did that, we would be able to vaccinate the world as quickly and as effectively as possible.

But further, we’d have additional protections. If it turns out that the Omicron variant requires a reformulated vaccine, let’s say, then we’re all back to zero. We’re all starting again. And in that case, too, the mRNA technology is among the very best in order to adapt into a new formulation. It’s faster to do it, and it’s easier to do it with an mRNA vaccine. And so, getting a lot of companies around the world — in Africa, Latin America and Asia — prepared, not just to withstand the current moment but future moments, will be just the very best solution in this pandemic.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Achal Prabhala, explain what’s going on. I mean, you have Moderna and Pfizer, that are based in the United States, BioNTech based in Germany. You have the U.S. pouring billions into the development, for example, of the Moderna vaccine. And you have the chairman of Moderna, Noubar Afeyan, saying very clearly, “We will not go after any company that wants to reproduce our mRNA vaccine.” So, what exactly is the issue here? You also have the U.S., because they poured that amount of money into the research, can demand this of Moderna. With Pfizer, they promised to buy billions of dollars’ worth of vaccines. So, in both these cases, this was done with so much public money, and the chair of Moderna is saying any company can do this. So what is holding up these 100 companies from doing this? Actually the explicit sharing of the formula?

ACHAL PRABHALA: That’s right. So, these vaccines were created through public money — nearly $500 million of German public money from taxpayers to BioNTech, nearly a billion dollars in money from U.S. taxpayers through the government to Moderna, several billions of dollars after that in exchange for buying back vaccines at high prices. So these are very much the people’s vaccines. It’s just that they are private property.

Now, when the Moderna CEO says, “Oh, anyone can make the Moderna vaccine,” he’s being a bit disingenuous. This is like giving people the pieces of a Lego box, let’s say, without an instruction manual to make some very complicated puzzle and saying, “You figure it out.” It’s not really possible to do that. The way vaccines work and the way regulation around vaccines work is that they need to be made with authorization and a license. Moderna and Pfizer or BioNTech, they need to authorize companies to make their vaccine. They need to share an instruction manual as to how to do it. They need to share with them some degree of assistance in terms of the supply chain, all of the different things that you need to produce the vaccine. This is not as complicated as it sounds. This is merely a question of authorization and a small degree of assistance. And they could, in fact, even earn revenue off it. Nobody gets the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines in India. If we took them, they would get back a share of whatever we paid for them. So it’s a solution that works for everyone.

The problem is, what it does is that it loosens Moderna and Pfizer and BioNTech’s stranglehold on these vaccines at the moment. It undercuts the massive tens of billions of dollars of profit and revenue that they can earn off selling to poor countries in the next couple of years, once they’re done with rich countries. And it seems that they don’t want that to happen and will do as much as they can not have it happen, which is why we’re asking the U.S. and German governments instead to say, “Look, in the face of this intransigence, it’s time to use emergency laws, that exist, that you can use, that you have the moral and legal power to put into effect, and end this pandemic for us and bring us out of this incredible cycle of hell.”

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Achal, though, could you respond to some of the early concerns about these vaccines being manufactured in countries outside Europe and North America, the U.S., and concerns about how these vaccines could be administered outside these countries — first, the concerns about the fact that they have to be kept at massively subzero temperatures, and what countries have the capacity to do that for large numbers of mRNA vaccines, transporting these vaccines, and then, lastly, the question of maintaining quality control, where these vaccines are being produced? So, could you talk about that, the quality issue, and the fact that some of the companies that you identified are already producing drugs that are being used in Europe and North America?

ACHAL PRABHALA: All very good questions, Nermeen. Firstly, mRNA technology is rapidly evolving. We are soon going to have what are called thermostable vaccines, which only need ordinary refrigeration. Even the original refrigeration marks for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccine have been revised. They don’t need as stringent refrigeration as we thought initially.

Now, in terms of quality, it’s always been the case that people have suspected, even within India, quality standards in India or in countries in sub-Saharan Africa or in Latin America, their own countries’ regulation. However, the companies that we’ve chosen here have all made an exactly similar product to a vaccine, but not only have they made it, they’ve exported it, to the United States, to the European Union and to the WHO, all of which, in the process of that export, had to examine their facilities and certify them for having the highest international quality standards of what they call good manufacturing practices. So these are companies that are already making the things that go into your arms through injections, and they are absolutely, certainly capable of doing that again with mRNA vaccines and really solving a pandemic not just for the countries in which they’re based but for you, for everyone, for all of us, if only they were allowed to.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally — we just have 20 seconds — what is the most important thing that President Biden here in the United States could do to make this happen?

ACHAL PRABHALA: President Biden can bring Moderna to the White House, sit them across the table, say that we have laws that can force you to do what we are asking you to do, but we’d rather you just do it instead, work out that agreement, and then let it go and take credit for vaccinating the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Achal Prabhala, we want to thank you so much for being with us, coordinator of the AccessIBSA project, which campaigns for access to vaccines, medicines in India, Brazil and South Africa.

Next up, we look at what Afghanistan faces, this looming humanitarian catastrophe, after the Taliban seized power and the U.S. and other donors cut off financial aid. We’ll speak to New Yorker staff writer Steve Coll, his new piece, “The Secret History of the U.S. Diplomatic Failure in Afghanistan: A trove of unreleased documents reveals a dispiriting record of misjudgment, hubris, and delusion that led to the fall of the Western-backed government.” Stay with us.