This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

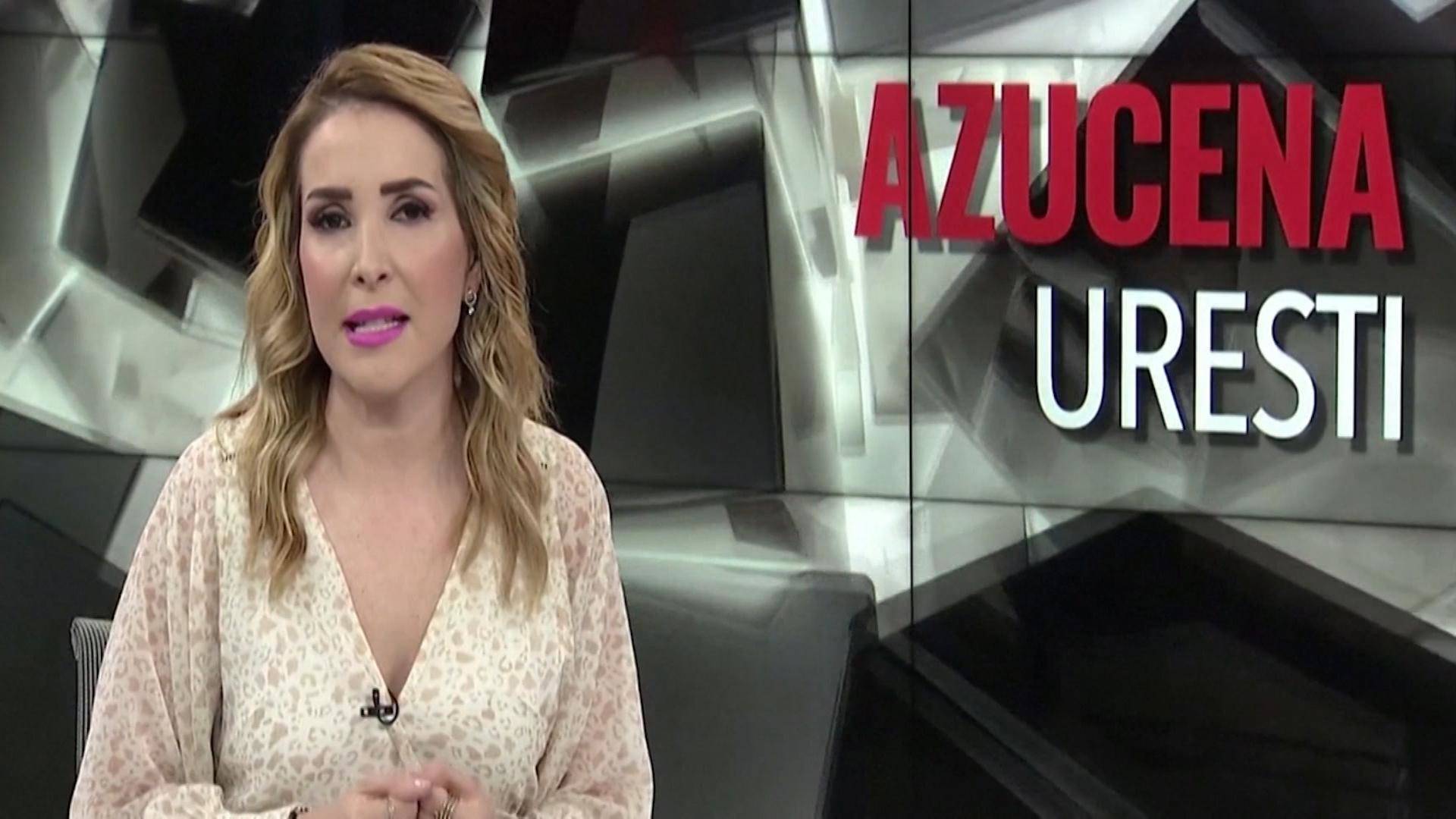

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman, as we go to Mexico, where prominent news anchor Azucena Uresti took to the airwaves to stand up to one of the country’s most powerful drug cartels.

Earlier this week, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel posted a video online in which they directly threatened Uresti, an anchor for the outlet Milenio TV and a radio broadcast for Radio Fórmula, who regularly reports on cartel violence and organized crime in Mexico. In the video, a man told Uresti, quote, “I assure you that wherever you are, I will find you and I will make you eat your words even if they accuse me of femicide.” The blurry video, which was posted on Twitter by an anonymous user, shows masked men carrying automatic rifles and other firearms.

Uresti addressed the threats during her broadcast Monday night.

AZUCENA URESTI: [translated] I have joined the federal system of protection from the government. I repeat: Our work will continue to be based on the truth and with the intention of providing information on the reality of a country like ours. And also, as has happened on other occasions, I express my solidarity and support to hundreds of colleagues who are still threatened or who have had to leave their areas, but who keep on showing the value of information and their love for this profession.

AMY GOODMAN: Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador vowed to protect Uresti.

PRESIDENT ANDRÉS MANUEL LÓPEZ OBRADOR: [translated] I completely reject these threats. We don’t accept this sort of behavior. We are going to protect Azucena, and we’re going to protect all Mexicans. It is our responsibility.

AMY GOODMAN: According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Mexico is the most dangerous country for journalists in the Western Hemisphere. Some 120 journalists have been killed in Mexico since 2000, with at least four murdered this year alone.

Well, for more, we go to Mexico City, where we’re joined by Jan-Albert Hootsen, Dutch journalist and Mexico correspondent at the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Jan, thanks — Jan-Albert, thanks so much for joining us. Why don’t you start off by talking about this situation of Uresti? Remarkably brave, after this death threat comes in, for her to go on the air and challenge the cartel, not only in her name, but in the name of all Mexican journalists trying to do their work on the ground.

JAN–ALBERT HOOTSEN: Absolutely. We believe the threat actually originated in an interview that she did on Radio Fórmula with a member of a citizen militia in the state of Michoacán, where the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cártel is currently embroiled in sort of gang-level warfare over territory in a traditionally very violent area in Mexico.

And I think it’s been a very clear message from the cartel that they want to manipulate and influence public opinion. I mean, it’s sort of a low-intensity civil conflict. It’s war for them. It’s a war against other criminal groups and against the state in Mexico. And with that comes a kind of information warfare. So, they were very clearly not happy with the way certain news outlets, certain national news outlets, were extensively covering the conflict, as Azucena had been doing for over the past few months, and they’re trying to manipulate that. They’re trying to change it.

They’re trying to strike terror in the hearts of Mexican reporters. And that’s sort of the goal of the video. They obviously knew that it was going to go viral. They obviously knew that Mexican outlets were going to reproduce the video and make the message spread across the country like wildfire. And that’s what happened, ultimately.

AMY GOODMAN: So, she has said, in her statement on the air, that she’s under federal protection. What does that mean? And what about the significance of AMLO, of the Mexican president, speaking out?

JAN–ALBERT HOOTSEN: So, when she says she is under federal protection, it essentially means that she has been incorporated into an agency of the federal government called the Federal Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists. And it’s an agency that coordinates protective measures, organized by the federal government, anywhere in the country, and it might range from getting a panic button or getting a bulletproof vest, a camera installation at her home, etc. So, there’s a whole catalog of protective measures that the government is able to provide. Some of them are a little bit more effective; some of them are a little bit less.

And it means that she will probably has some — she’ll have to limit her movements a little bit. She’ll have to check in with the federal authorities every once in a while. And it also means that the federal government will need to see what they can do further to investigate this threat, because, ultimately, the threat stems from Jalisco or from Michoacán. These are states in the center of Mexico. They’ll have to investigate and see what they can do about that, because, obviously, protective measures can only go so far.

AMY GOODMAN: So, can you tell us what Azucena Uresti was actually investigating as this threat came in, and then put it in the context, overall? In June, one of the murderers of Mexican journalist Javier Valdez was sentenced to 32 years in prison. He was murdered in 2017. His colleague, Miroslava Breach, was assassinated just two months before him. I want to play a clip of Valdez speaking at the International Press Freedom Award from your organization, the Committee to Protect Journalists, in 2011, New York. And then you can tell us each of their stories.

JAVIER VALDEZ CÁRDENAS: [translated] I have been a journalist these past 21 years, and never before have I suffered or enjoyed it this intensely, nor with so many dangers. In Culiacán, in the state of Sinaloa, Mexico, it is dangerous to be alive. And to do journalism is to tread an invisible line drawn by the bad guys, who are in drug trafficking and in the government, in a field strewn with explosives. …

This is a war, yes, but one for control by the narcos. But we, the citizens, are providing the deaths, and the Mexican and U.S. governments, the guns. And they, the eminent, invisible and hidden ones, within and outside of the governments, they take the profits.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that’s Mexican journalist Javier Valdez, before he was murdered. Now one of the murderers was sentenced to 32 years in prison. But how rare is that even to find someone who has killed a journalist? And give us all the numbers.

JAN–ALBERT HOOTSEN Sure thing. Circling back to your first question, broadly speaking, Azucena Uresti and Milenio Televisión and her radio show on Radio Fórmula were covering a conflict in a specific area of Michoacán in the center of Mexico, where a number of organized crime groups have united to fight back against an incursion of the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cártel. And particularly what may have set this threat off was an interview that she did with a member of one of those self-declared self-defense groups in the area where the person who she was speaking with was using relatively strong language in reference to the leader of the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cártel. There might have been a little bit of ego involved there, but it appears to be the one issue that set this all off.

And, you know, in a broader context, as you mentioned, Mexico is the most dangerous country for journalists in the Western Hemisphere. It has been so for a very long time. More than 120 journalists have been murdered since CPJ started taking numbers, started gathering statistics on violence against the press in 1992. More than 95% of these murders linger in impunity. It’s very rare, actually, for Mexican authorities to even arrest someone in crimes against the press, let alone sentence them.

So what happened in the cases of Javier Valdez and Miroslava Breach was relatively rare, and it really only happened because the Mexican state invested a relatively large number of resources and a lot of time in investigating these murders, because it was a PR problem for them, really. They couldn’t really stand back and not do anything.

And both Javier Valdez and Miroslava Breach were correspondents for the newspaper of La Jornada, which is a newspaper, a progressive one, based in Mexico City. Javier Valdez was also the co-founder of a weekly magazine called Ríodoce in the city of Culiacán in the northern state of Sinaloa. He was well known for writing columns about organized crime, and especially about human rights and about how it’s really like for people in Sinaloa to live in the shadow of drug trafficking groups. In the case of Miroslava Breach, she was a correspondent for La Jornada in the northern state of Chihuahua, and she was widely known in Mexico for investigating the ties between local criminal groups in Chihuahua and political parties.

So, both of them were, in reality, killed because they angered specific criminal groups. In the case of Javier Valdez, it was a group belonging to the Sinaloa Cartel. In the case of Miroslava Breach, it was another group belonging to the Sinaloa Cartel that was active in Chihuahua. So they were both killed because of that.

And to give you another idea of what the situation is like in Mexico, after their murders in 2017, four years ago, between 30 and 40 reporters were killed in Mexico. Most of them have never been — most of those murders have never actually been solved.

AMY GOODMAN: How can they best be protected, Jan-Albert?

JAN–ALBERT HOOTSEN That’s a very good question. And the best way for them to protect them, it’s sort of like a two-pronged solution. One of them is the Mexican government should actually vastly expand the existing protective mechanisms that they have. They should better train the people focused on human rights in their government and coordinating these protective measures. That, in itself, is quite a task, because the Mexican government has actually never done so adequately.

But the other one — and it’s incredibly important — is they should fight impunity, because, ultimately, the best way to protect journalists is by preventing these things from ever happening. And the best way for preventing these things from ever happening is by fighting back, by arresting people, by letting these criminals know that if they actually do kill a journalist, they’re going to get caught, and they’re going to go to jail, because impunity is what keeps incentivizing this. But, unfortunately, neither of those things is done sufficiently by the Mexican government.

AMY GOODMAN: Jan-Albert Hootsen, I want to thank you so much for being with us, Dutch journalist, Mexico correspondent at the Committee to Protect Journalists, speaking to us from Mexico City.

Coming up, we speak to healthcare activist Ady Barkan about fighting for Medicare for All after ALS has left him paralyzed and without use of his voice. A new documentary about his life is premiering this weekend, called Not Going Quietly. Stay with us.