This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

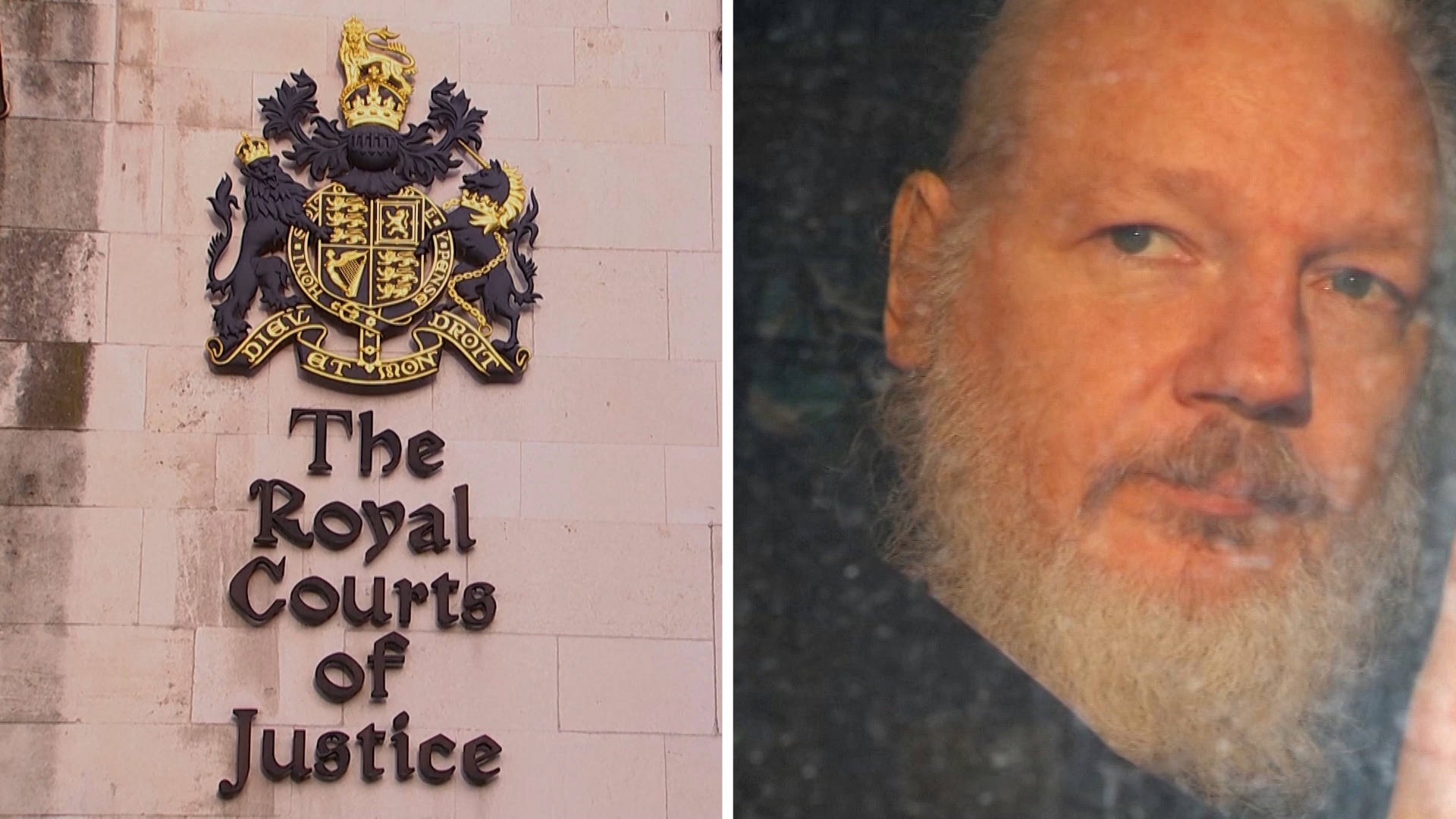

AMY GOODMAN: WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange could soon face criminal charges in the United States after a U.K. court ruled this morning in favor of the U.S. government’s appeal to extradite him. Assange faces up to 175 years in prison in the United States under the Espionage Act for publishing classified documents exposing U.S. war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan. Assange has been jailed in England for two-and-a-half years. Before that, he spent over seven years in exile in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. There he had been granted political asylum.

A London district judge had ruled in January that Assange should not be extradited because it would be “oppressive” due to his mental health, and that he would likely die by suicide in a U.S. prison. But in a ruling issued this morning, British Judge Timothy Holroyde said he was satisfied with a pledge from the United States that Assange would not be held in a so-called ADX maximum-security prison in Colorado. According to court documents, the U.S. won its appeal to extradite Assange due to, quote, “four assurances” sent in a diplomatic note in February, which include the condition that, quote, “the United States retains the power to designate Mr Assange to ADX in the event that, after entry of this assurance, he was to commit any future act that then meant he met the test for such designation.”

Outside the court, supporters rallied for Assange’s release. This is Christophe Deloire, secretary-general of Reporters Without Borders.

CHRISTOPHE DELOIRE: We do defend Julian Assange because he is prosecuted for his contribution to journalism. And his extradition would clearly have long-standing and severe implications regarding press freedom all over the world, in this country, in the U.S. and beyond. And that’s why there is only one legitimate option now, which is that the case is closed and that Julian is immediately released. And I take the opportunity to call on the journalists everywhere to be totally conscious of what happens now, of what is now considered. It’s really the crucial moment for all journalists everywhere to defend journalism, to defend Julian in this case. So, really, act now. Act before it’s too late.

AMY GOODMAN: The British court’s ruling comes as the Biden administration is hosting a global Summit for Democracy, where Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced U.S. efforts to support independent journalism and reporters targeted for their work.

SECRETARY OF STATE ANTONY BLINKEN: We’re asking governments to make concrete commitments to strengthen free, independent media and help tackle the diverse challenges that they face. … We’re increasing protection for the free press here at home. In July, the Department of Justice adopted a new policy to stop using subpoenas, warrants and other investigative powers to obtain notes, work products or other information from journalists engaged in newsgathering activities.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we’re joined by Gabriel Shipton, who is Julian Assange’s brother and a filmmaker, and Ben Wizner, director of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy and Technology Project, also the legal adviser to NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden.

We welcome you both back to Democracy Now! Jeff, let’s begin — Ben Wizner, let’s begin with you. Your response to the ruling by the High Court in Britain?

BEN WIZNER: Well, obviously, anything that brings Julian Assange one step closer to a courtroom in the United States is a terrible step. But it’s important to note that only one issue was at stake in the appeal today, and that was the judge’s earlier ruling that Julian Assange should not be extradited because of the oppressive conditions of confinement that he would be exposed to that would present a suicide risk.

What was not at stake in this appeal is the much more significant legal issue for global press freedom. And that is: Can charges under the U.S. Espionage Act result in the extradition of a foreign publisher for publishing truthful information? And this is the issue that really journalists around the world should be watching more closely, and journalists in the United States, in particular, should be a lot louder about, because whatever they may think about WikiLeaks and however they may want to choose to find themselves in contrast to WikiLeaks, this is a precedent that is going to affect every investigative journalist in the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: And let me get the response of Gabriel Shipton. You are Julian Assange’s brother. You’re a filmmaker. We’ve had you on before with your father talking about this case. Your response to this breaking news that Julian Assange could be now sent to the United States, though there’s still a few other legal steps that have to happen?

GABRIEL SHIPTON: I don’t think we can ignore any longer that, you know, we can rely on the British courts to stop this extradition. The charges against Julian need to be dropped by the Biden administration and the Merrick Garland DOJ here in the U.S. I mean, Julian, he’s been — you know, it’s been 11 years since he was first arrested in the U.K. You know, this is going to be his third Christmas in Belmarsh maximum-security prison. He’s only being held in Belmarsh at the request of the U.S. DOJ. He is not serving a sentence. The DOJ has — you know, they’re requesting that bail is not given to Julian. So, really, what needs to happen now is the Biden administration needs to drop these charges and let Julian go.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the five appeal points that were heard in this case, how Julian is right now in Britain, and what you think would happen if he were brought to the United States?

GABRIEL SHIPTON: Well, I think the appeal was approved based on the assurances given by the U.S. These assurances have been found — you know, Amnesty International has said they’re not worth the paper they’re printed on. If he’s extradited, he, I’m sure — you know, they can’t guarantee his safety in the U.S. prison system. He will likely die here, if not beforehand. So, that’s — really, we live in fear of that happening to Julian.

And as I said, it’s his third Christmas in Belmarsh prison now. You know, the conditions there, they’re not good there, either. He should be at home with his family. He’s just — you know, he’s being crushed, basically. And I’m so — you know, it’s hard to — it’s hard to put into words, really, what we’re seeing happening to Julian. He is so strong and so resilient, but this whole process has really taken its toll on him.

AMY GOODMAN: Ben Wizner —

GABRIEL SHIPTON: The next —

AMY GOODMAN: Oh, go ahead.

GABRIEL SHIPTON: So, the next stage, so Julian has now two weeks to appeal this decision. The High Court has ordered the magistrates’ court to approve the extradition and send it to Priti Patel to approve. So Julian has two weeks to appeal this decision. And we’re going to keep fighting. We’re going to appeal. And there is also a cross-appeal in the works, which will appeal all the substantive press freedom issues, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, I’m looking at the Amnesty statement, Gabriel, and it says, “They say: we guarantee that he won’t be held in a maximum security facility and he will not be subjected to Special Administrative Measures” — those are called SAMs — “and he will get healthcare. But if he does something that we don’t like, we reserve the right to not guarantee him, we reserve the right to put him in a maximum security facility.” Gabriel?

GABRIEL SHIPTON: Yeah, that’s right. And, you know, the person who makes this decision is the director of the CIA. And so, you know, in September, we saw an exposé by Yahoo News investigative journalists that found there were plots within the CIA to kidnap, to murder Julian. So, really, what he’s being put — his health and well-being and he’s being put in the hands of the people who had plots to murder and kidnap him. So these assurances, like I said, they’re not worth the paper they’re printed on. They’re not assurances at all.

And I think you can see what’s happened with whistleblower Daniel Hale. He’s been put in what’s called a CMU, a Communication Management Unit, which is — you know, it’s almost worse than ADX Florence. So, there’s all these options that they have, that the prison system has at their disposal to restrict Julian’s communication, to restrict his ability to communicate with other people in the prison, and just really to grind him down to dust, basically.

AMY GOODMAN: Ben Wizner, we’re about to play the Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech of Maria Ressa. She and the Russian journalist Muratov got their awards today as the Nobel Committee in Oslo talked about celebrating freedom of expression. You’re deeply concerned about this issue with Julian Assange. Is he the first publisher to face espionage charges like this in the United States? And what are the plans? ACLU has signed on to letters. What are the campaigns planned right now as this process moves forward? And if you could specifically address what Julian released, this whole issue of the Afghan War Logs, the Iraq War Logs and decades of State Department communiqués and memos, what this information has meant for journalism in the United States, for the United States and the world, talking about what happens on the ground in war?

BEN WIZNER: So, that’s a lot, but I’ll do my best, Amy. First of all, yes, this is the first time in the 100-year ignominious history of U.S. Espionage Act, which was passed during an earlier Red Scare, that someone has been prosecuted with felony charges for publishing truthful information. We’ve never seen a case like this. This was a Rubicon that we didn’t want to see crossed. The Obama administration considered making Julian Assange the first person charged, convened a criminal grand jury, but, at the end, cooler heads prevailed, and they realized that there was simply no way to distinguish the conduct that they would have to charge in this case from what investigative journalists at The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker do on a daily basis.

And let’s remember, this case involves disclosures from 2010, 2011, that Chelsea Manning was convicted for providing to WikiLeaks. This was not something that WikiLeaks published on its own. WikiLeaks partnered with The New York Times, with Der Spiegel, with The Guardian. And those newspapers published award-winning journalism covering war crimes that the U.S. and U.K. military had committed in Iraq and in Afghanistan, diplomatic cables that shed light on our support for oppressive regimes and torture and contributed to the Arab Spring. So this was really vital information that the public around the world had a right and a need to know.

And here’s our concern. At the U.S. level, this indictment criminalizes investigative journalism. Now, the Justice Department wants to say this isn’t journalism, this is a criminal conspiracy; he conspired with Chelsea Manning, tried to urge her, cajole her, help her to turn over U.S. government secrets. But that precisely describes what our best investigative journalists do. You could describe everything they do as a criminal conspiracy, because they’re trying to persuade people with access to privileged and important information to violate the law and turn it over to journalists in the public interest. So, this precedent, if there is a conviction here, will chill journalists. It doesn’t mean that The New York Times will be prosecuted the next day, but it means their lawyers will tell their journalists that they can’t publish important things because of that threat of prosecution.

But there’s another element here that I think ties more to the global press freedom issue. And it is ironic that it’s happening on the same day that these Nobel Prizes are being awarded. And that is that the U.S. is taking the position that our secrecy laws apply criminally to foreign publishers, that someone who has no ties to the United States, who is publishing overseas, making his own determinations of public interest considerations, can be hauled into — extradited and hauled into a U.S. court and prosecuted. And think about what that precedent will mean around the world if every regime now can point to us and say, “We want to extradite these journalists.” Viktor Orbán wants to extradite Guardian journalists to Hungary because they published Hungarian secrets. You know, the Chinese want to extradite New York Times journalists because they published Chinese secrets, which The New York Times does routinely. And again, the threat is not that the U.S. will have to send its journalists to China — it will never do that — but that we are now embracing and blessing and setting this precedent that is going to empower the worst authoritarian forces around the world.

So, look, I take what Gabriel says. I think we are still hoping that the U.K. courts will find a way to resolve this case without setting the precedent that a foreign publisher can be extradited to the United States. If that doesn’t happen, it will be all hands on deck in the U.S. You know, of course, we will be appealing again to the Merrick Garland Justice Department to find some kind of face-saving resolution here that doesn’t involve setting this kind of precedent that will smear their own reputations. And if that doesn’t happen, all of these groups will be in court as friends of the court arguing strenuously that this is an intolerable prosecution under the First Amendment.

AMY GOODMAN: Ben Wizner, we want to thank you for being with us, director of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy and Technology Project. We also want to thank Gabriel Shipton, Julian Assange’s brother and filmmaker. To see all our conversations with Julian Assange, including the ones where we went inside the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, where he was in political exile, before being sent to the Belmarsh maximum-security prison, go to democracynow.org.

Next up, two journalists have just received the Nobel Peace Prize today in Oslo. You will hear the speech of Filipina journalist Maria Ressa. Stay with us.