This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

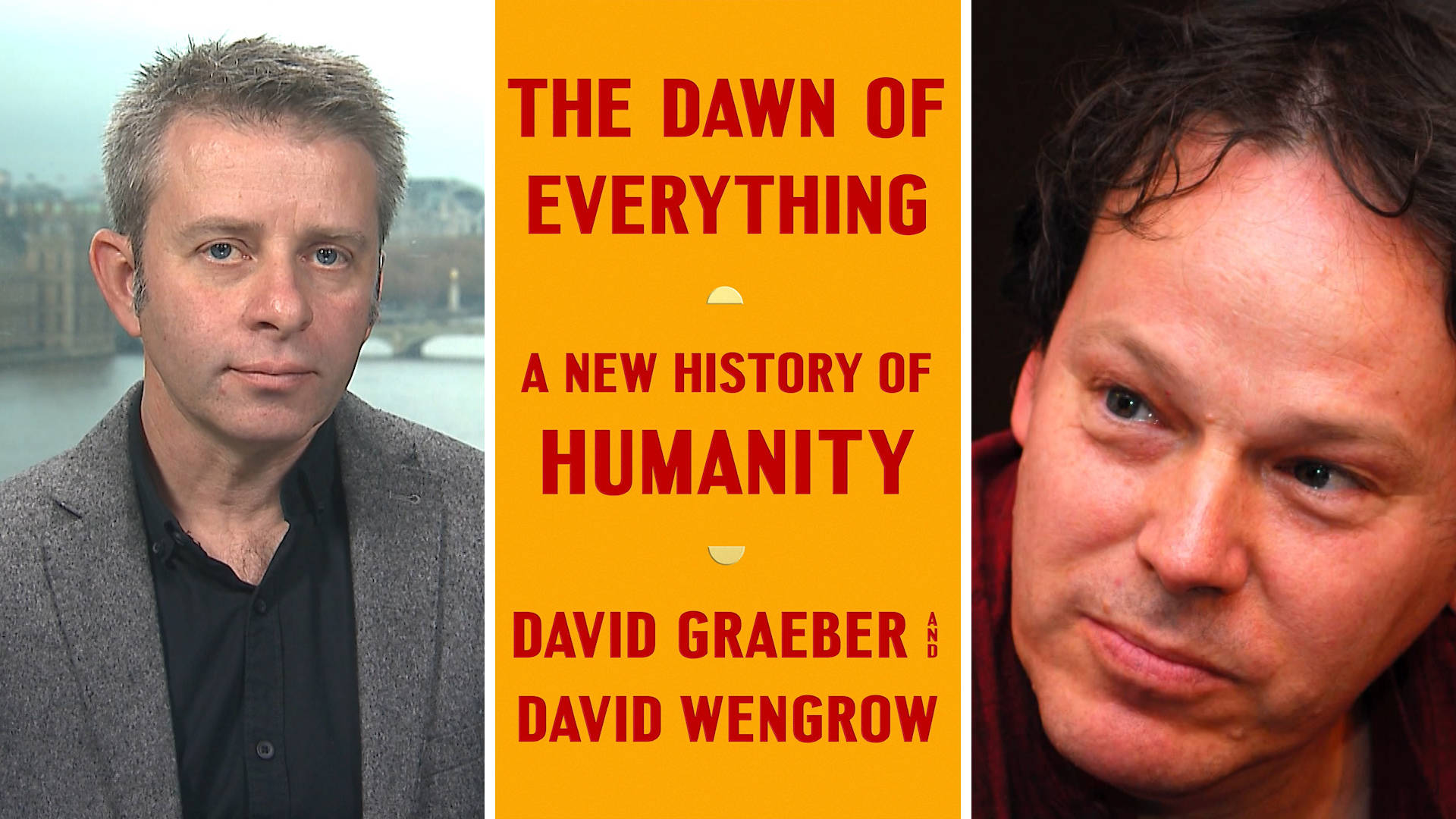

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, Democracynow.org, the War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman with Nermeen Shaikh. We turn now to a groundbreaking new book. It is titled The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. It is written by the late anthropologist David Graeber and the archeologist David Wengrow. The book examines how indigenous cultures contributed greatly to what we have come to understand as so-called Western ideas of democracy and equality but these contributions have been erased from history.

After years of research, the two men completed the book in the summer of 2020 just weeks before David Graeber died unexpectedly at the age of 59 on vacation in Venice, Italy. Graeber was a highly influential anthropologist, a veteran of the international anti-capitalist movement that pushed for a different vision of globalization. His book Debt: The First 5,000 Years made the case for sweeping debt cancellation. He also helped organize the Occupy Wall Street protest on September 17, 2011 and was credited with helping to coin the phrase “We are the 99%.” In both his academic and activist work, David Graeber looked at ways to radically recreate society. This is David Graeber speaking on Democracy Now! just two days after Occupy began.

DAVID GRAEBER: I ended up facilitating a meeting which was at least 2,000 people. It was mostly young people and most of them were people who had gone through the educational system who were deeply in debt and who found it completely impossible to get jobs. These people really feel very strongly that they did the right thing, they did exactly what they were supposed to and the system has completely failed them. They’re not going to be saved by the people in charge. If there is going to be any kind of society worth living in, we’re going to have to create it ourselves.

AMY GOODMAN: That was the late David Graeber in 2011. We are joined now by his dear friend and co-author, David Wengrow. The two co-wrote The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. David Wengrow is joining us from London where he is a Professor of Comparative Archaeology at University College London. David, thanks so much for joining us. Our condolences on the death of David just as you finished this book. David lived just down the street from Democracy Now! studios in the ILG houses, the International Ladies Garment Workers housing complex that is just about a block from here, which so much shaped him. Just start with the title, The Dawn of Everything and this new narrative that you both want to bring to the world.

DAVID WENGROW: We really started exchanging ideas around the time that you were describing, the time of the Occupy movement, so around 2011. We exchanged books. David gave me the debt book that you mentioned. I gave him a book I had written on ancient civilizations. We started swapping ideas. We were interested in how our fields—I am an archeologist and as you mentioned David was an anthropologist—how we could contribute to debates on social inequality which had really been escalating since the financial crash of 2008.

Initially, we planned to write something quite short, really a sort of pamphlet, just to introduce readers to major discoveries from our fields that we felt hadn’t really escaped out of the academy into wider consciousness. Firstly, this very conventional idea that before human beings invented agriculture we lived almost exclusively in tiny egalitarian bands of hunter-gatherers, it is not true. It is actually wildly inaccurate. There simply was no such period of prolonged political innocence. Secondly, the equally conventional and entrenched idea that our species became trapped in inequality through the invention of agriculture and then later cities, that is not true either. Actually, what the broad sweep of history shows is that living in large-scale densely populated technologically sophisticated societies really doesn’t require people to simply give up social freedoms in the way that we are often told it does. As you can probably gather by now, this was already getting beyond a short pamphlet.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: David, one of the critical points that your book makes is that the encounter between indigenous intellectuals and early European colonists was very important to what we now refer to as the Enlightenment, ideas of democracy and of inequality. One of the central figures you name is Kandiaronk, a late 17th century indigenous intellectual. Could you explain who he was and what his example illustrates about this broader history of the encounter between European colonists and indigenous peoples?

DAVID WENGROW: Yes. It goes back to the first question, really. We realized there was something fundamentally strange about the fact that human history is conventionally framed in this way about a question about the origins of inequality. Where does the question come from? It already assumes that there is something else, an age of equals or an age of freedom. Tracing it back to its origins, they really go back to an essay competition. In 1753, a French academy poses that question: what is the origin of social inequality? Reflecting on this, we realized this is strange. We’re talking about France before the Revolution, one of the most hierarchical societies on Earth. Why do people already assume that things were once different?

Following that line of inquiry led us to the Americans and this encounter between European colonists and indigenous societies, particularly around the region of the Great Lakes of what is now Canada. It was in that area that Europeans first encountered entire societies built on principles of social freedom that were still completely alien to European civilizations at the time. Kandiaronk was very much a product of that social milieu. He was a leading figure in Wendat society at the time. He was one of the signatories in 1701 of the Great Peace of Montreal. Apart from being a warrior and a diplomat, he was clearly regarded by almost everyone who met him, Europeans and indigenous people, as simply one of the most intelligent people they had ever met, a great thinker, a great orator. He was routinely invited to the fort, the table at the then French governor of that part of the colonies, to engage in debates with Europeans on topics that ranged from Christianity to marriage customs, the role of money and whole idea of political freedoms.

Many of these conversations were recorded and in them, Kandiaronk launches a truly stinging critique of European behavior. There’s a lot about women’s freedoms. There’s a lot about the obsession with wealth and money as forms of power. There are many observations on poverty and the kind of endemic homelessness that was apparent already then in European towns, colonial towns included. And there’s a lot of discussion, a lot of criticism of the way that Europeans are constantly on the one hand competing with each other but also deferring to each other on the basis of rank and status, which seems to have been a principle that was alien and absent from Iroquoian-speaking societies at the time.

If a Wendat chief wanted to engage people in some kind of collective project, there was no real way to command or coerce, so it was all really predicated on persuasion. It was widely observed by Jesuit missionaries and others at the time that people would sit in the village plaza for long hours each day debating and trying to convince each other and reach consensus on the issues of the time. It is actually not contested that Europe in the age of Enlightenment adopted important cultural habits from the Americas, smoking tobacco from pipes, drinking caffeinated beverages. But for some reason, it never seems to occur to historians to ask if we also borrowed concepts and ideas. In the book, we try to show that that is exactly what happened. Kandiaronk is really a product of that culture, which influenced Europe in quite profound ways.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: One of the things that is very striking about the book is precisely what you say here, that there was from Kandiaronk and presumably others too these critiques of European society at the time. Could you explain why you think these critiques have been all but entirely erased from the historical records?

DAVID WENGROW: It’s a very interesting question because from time to time, over the last few decades, historians, some of them like the historian Georges Sioui, who is in fact himself of the Huron-Wendat nation with a PhD in history, have drawn attention to these sources. But for reasons that I can’t really explain that really reflect I think very poorly on our institutions and on the academy, they have been marginalized. One thing we tried to do in our book is really shine a light on that existing scholarship.

AMY GOODMAN: I would like to go back to 2018 when David Graeber talked about The Dawn of Everything. It was during a teach-out outside your school, the University College London.

DAVID GRAEBER: We started saying, well, maybe the inequality question—if we just move that aside, the real question isn’t where did the inequality come from or where did the hierarchy come from. It’s like how did we get stuck in one mode? Because it’s very different having a police force and you’re going to be on the police force this year but next year you won’t and the year after that you will. People aren’t going to behave the same in a hierarchy if the hierarchy is going to get ripped down for half the year and everybody has to deal with each other as equals.

AMY GOODMAN: That is the late David Graeber. David Wengrow, you were sitting right next to him outside your school. If you can explain the current debates about both democracy and equality and how they are really explained differently in The Dawn of Everything, in this new history of humanity.

DAVID WENGROW: It is interesting and a bit painful to listen to that clip for many reasons, one of which is that we’re going to be on strike again in a few weeks’ time over exactly the same issue. What David is describing there is one of the major things that came out of our research, which is that human beings for most of the history of our species have simply been a much more playful and experimental species than we tend to give ourselves credit for, including a propensity to simply invent and experiment with different forms of political arrangements.

Once you realize this is the case, the question itself changes. We start thinking differently about the big questions of human history. If it is not about the origins of inequality, so if we do away with this false notion that there was once this society of equals, what is it then about? What David is talking about in this clip is really the other question that then comes into view, which is how did we get stuck in a situation where these days we find it almost impossible to even imagine, let alone put into effect, other forms of social arrangements. And how stuck are we, really, in that respect?

I think the first step towards answering that question is precisely to examine the big story that we tell about the history of our species and about human capacities in general. What we’re trying to do in the book is really blow away the cobwebs of all these outdated theories and basically myths which persuade us that the kinds of inequality we have today are in fact an inevitable result of social evolution. Once you take those things away, what you’re left with is really people making everyday decisions. That in itself seems to us an important step in getting unstuck.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the argument you make around war and competition, that it is not evolutionarily rooted in human beings, it is not inevitable. Talk about this different view of history when it comes to war.

DAVID WENGROW: When you look directly at the evidence—and we do have pretty good evidence, direct evidence these days—for things like rates of violence and interpersonal conflict and injuries in the archaeological record, the way I would put it is that yes, warfare and violence can be traced very, very far back to the history of our species, but they are no more inevitable in that body of evidence than periods of peace. Periods of violence and war come and they go, so one can’t say that we are innately warlike and competitive any more or less than you can say we are innately altruistic and cooperative.

The question which really emerges from the book is why it is that at certain points in history, violence, including warfare, has a more profound and durable effect than at others. In other words, why passing acts of violence, which are obviously always traumatic, but they don’t always become structural. They don’t always become embedded in the fabric of homes and family life, some of the other things you have touched on already in your show today. That became a real focus of the book and a focus of trying to understand how it is that our societies have gotten to the stage where we do feel trapped and stuck. Simply by diagnosing the problem better, we feel that in itself is important in reflecting on how one can then untangle oneself from those kinds of violence.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Could you explain, David, from David Graeber’s clip that we just played, how this conception of war and violence also has something to do with the fact of hierarchies being fluid in the way that your book shows and that David spoke about, that people who occupied powerful positions did not occupy them in perpetuity, meaning not even in the same year, that there was a constant shift between those who were in power and those who were not?

DAVID WENGROW: That’s right. This is an excellent example of what I was talking about in the sense of the experimental nature of human politics. When we think about hunter-gatherer societies, we tend to think of perhaps one or two basic forms of egalitarian society. Actually what we found is that there’s really a large literature on societies—some of them practiced agriculture, some did not—that actually used to flip or alternate their social systems on a seasonal basis. One of the examples in the book which David was referring to there were the Plains Nations of North America, at a certain time of year—it was the time of year when the bison and the buffalo came through on their seasonal migrations—would form into a kind of society that in some respects resembles what we today would call a state. There was a police force. There were squads of soldiers who had full coercive powers. If anyone endangered the success of the hunt they could be whipped, they could be imprisoned, they could even be killed.

But the point about this—well, there are two points. First, the individuals who occupied those roles, those coercive roles, rotated on an annual or biannual basis, so you could actually be confronting the person who you’ve whipped, imprisoned, punished the next year but from the other end of the process. The second is that these societies with their coercive institutions didn’t last beyond the period of the hunting season and the Sun Dance rituals which followed, and actually for the rest of the year, these Plains societies would split off into demographically smaller groups which had entirely different moral systems and actually where coercion wasn’t permitted and people would have to resolve disputes through processes of deliberation and debate.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: You write also in the book, just to look at the context of the arguments that you make in this quite monumental work, 700 pages long, that the book began as an appeal to ask better questions. As academics, journalists, activists committed to social justice and greater levels of equality, what are the questions that we should be asking?

DAVID WENGROW: As you mentioned, David was deeply involved in the global justice movement. At least as I perceive it, the central question of that movement is whether our current cultural system, with all of its issues including issues of sustainability and the climate crisis, whether this is really basically the only way that we can organize our societies today or whether there are in fact viable alternatives. As an anthropologist and an archaeologist, a very logical thing to do is then to simply look at all the other ways that humans have in fact organized themselves over the whole span of our species’ history.

When you do that in the light of modern scientific evidence, other questions and other possibilities do in fact come to light. For example, questions about sustainable cities, actually it turns out that for many centuries or even thousands of years, we have evidence now of really large-scale densely populated societies which lived in cities that were essentially decentralized in terms of their decision-making processes. We have examples of mass societies which managed to organize themselves without reducing people to numbers in a queue, so they don’t have the kind of impersonal bureaucracies that we just sort of take for granted today and feel are kind of inevitable. We also have some really striking examples including one from pre-Columbian Central America, from Mexico, of systems of democracy which were based on the principle of containing one’s ego rather than flaunting one’s ego in the way that we’ve come to expect from—

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to have to leave it there, David. I thank you so much for being with us.

People can get it in the book by David Wengrow and the late David Graeber, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. I’m Amy Goodman with Nermeen Shaikh.